css button by Css3Menu.com

GLOSSARY OF NEUROLOGICAL TERMS & CONDITIONS

Index

Terminology – motor

Terminology – sensory

Upper motor neurone syndrome

Parkinson’s disease

Cerebellar disease

Communication and swallowing problems

Visual field defects

Cognitive problems

Perceptual problems

Behavioural changes

Psychological and emotional consequences

Bibliography

Why do I need this?

This is a quick reference guide of terms that you will come across in the module, when reading around the subject and on placement. You need to be able to explain what the terms mean in an exam situation and on placement to your clinical educators, your patients and their relatives.

Some students have found it useful to take the booklet on placement to improve their understanding of a particular term by comparing it with the clinical reality.

Terminology - Motor

Ballismus: abnormal large involuntary movements of the limbs or one limb (called hemiballismus)

Chorea: irregular spontaneous movements, often abrupt and can vary from restlessness to wilder erratic movements

Dyskinesia: impairment of voluntary movement, often leads to incomplete movements

Hemiplegia: paralysis of one side of the body, (including one side of the face and trunk) contralateral to the side of the lesion in the brain. It is frequently associated with sensory loss.

Monoplegia: paralysis affecting a single limb.

Paralysis: impairment or loss of muscle function

Paraparesis: weakness or partial loss of movement and or sensation in the lower half of the body following damage to the spinal cord in the thoracic, lumbar or sacral regions.

Paraplegia: The loss of movement and or sensory function in the lower half of the body following damage to the spinal cord in the thoracic, lumbar or sacral regions. (May be referred to as diplegia).

Plegia: a specialised type of paralysis

Quadriplegia/Tetraplegia: impairment or loss of motor and /or sensory function in the cervical segments of the spinal cord. The upper limbs are affected as well as the trunk, lower limbs and pelvic organs. It does not include brachial plexus lesions or injury to peripheral nerves. It is most frequently seen following a spinal cord injury to the cervical spine.

Spasm: a transient increase in tone in a muscle or group of muscles in the presence of neurological pathology

Terminology - Sensory

Sensory disturbance may result in a variety of symptoms that can be divided into negative and positive symptoms:

Negative symptoms: for example can be described as “a loss of feeling” or “a deadness”

Positive symptoms: can include a pins and needles sensation and a burning feeling

Other sensory related terms:

Allodynia: pain resulting from non-noxious stimuli, can be difficult to treat and often requires pharmacological treatment such as amytriptolene.

Altered sensation: every-day sensation is perceived differently e.g. as burning or pins and needles sensation, or the patient has sensation in the absence of any sensory stimulus - often burning or shooting sensations, pins and needles, or the feeling that water or insects are running over the skin. This can be very distressing and disabling.

Anaesthesia: complete loss of sensation resulting in numbness and loss of proprioception.

Astereognosis: a failure to discriminate objects held in the hand (stereognosis)

Causalgia: is an incomplete peripheral nerve injury producing intense, continuous, burning pain. Touching the limb aggravates the pain and resists having the limb moved. Limb may be red, swollen and hot.

Hemisensory loss: loss of feeling/sensation on one side of the body

Hyperaesthesia or hypersensitivity: perception of sensation is increased. This can mean that every-day sensations can be painful.

Paraesthesia: partial loss of sensation, abnormal sensations i.e. numbness, tingling, burning

Thalamic pain: a vascular event to the thalamus may result in pain that is exacerbated by the touch of clothing

Upper Motor Neurone Syndrome

Upper motor neurone syndrome refers to the range of clinical features that result from lesions to some or all of the long descending tracts that control or influence muscle tone and influence the excitability of the lower motor neurone (Sheean, 1998, Lindsay & Bone, 2004), e.g. stroke, traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury. The clinical features of UMN syndrome are divided into positive features, negative features and adaptive features (Carr & Shepherd, 2003).

Positive Features:

These are described as exaggerations of normal phenomena or release phenomena.

Spasticity: Classically this is described as: “ a motor disorder characterised by a velocity-dependent increase in tonic stretch reflexes with exaggerated tendon jerks resulting from hyperexcitability of the stretch reflex as one component of the upper motor neurone syndrome” (Lance, 1980).

The reflex threshold is lowered in patients with spasticity and the primary muscle spindle endings of Ia afferents, which are sensitive to the velocity of stretch; provoke greater muscle contraction in response to increasing speed of the movement/stretch. In this way spasticity provides a neural component to hypertonia (see below).

Clasp knife phenomenon: this is a term that describes the response to stretch of a muscle with spasticity. A rapid joint movement stretches the muscle and elicits a velocity dependent tonic stretch reflex. The resistance produced by the reflex contraction of this muscle slows the movement, therefore reducing the stimulus for the stretch reflex to below the velocity threshold. The muscle contraction therefore stops, quite abruptly, allowing the examiner who keeps up the tension to continue the movement with minimal resistance (Sheean, 1998).

Clonus: seen as a rhythmical contraction of the plantar flexors following a passive stretch. A brisk stretch of gastrocnemius and soleus elicits a stretch reflex, the gastrocnemius and soleus contract, plantarflexing the ankle and eliminating the stretch, and the muscle relaxes. If the relaxation is rapid and the stretch is maintained, another stretch reflex will be elicited and the ankle will plantarflex again setting up a sustained rhythmical contraction. This will continue as long as the stretch is maintained (Sheean, 1998).

Increased tendon reflexes: hyper-reflexia noted following tendon tapping e.g. tendoachilles, quadriceps. Radiation of reflexes may occur e.g. tapping of the tendoachilles may cause contraction of the quadriceps and adductors of the same leg.

Positive Babinski: an upward movement of the great toe into extension and abduction of the toes in response to stroking the sole of the foot in a lateral to medial direction with a blunt implement. The presence of a positive Babinski is an abnormal response and indicates upper motor neurone damage.

Negative Babinski: a downward movement of the great toe into flexion and adduction of the toes in response to stroking the sole of the foot in a lateral to medial direction with a pointed implement. A negative Babinski is a normal finding.

Extensor spasms: muscle spasms producing extension, medial rotation and adduction of the hip, knee extension with plantar flexion and inversion of the ankle and foot complex. Most commonly seen in patients with incomplete spinal cord injury, cerebral lesions e.g. stroke or head injury and multiple sclerosis. Primarily seen in the lower limb but can be exhibited in the upper limb/s. A transient spasm usually occurs in response to noxious stimuli.

Flexor spasms: muscle spasms of the hip, knee and ankle flexors occurring spontaneously or in response to cutaneous stimulation. The limb adopts a position of flexion, lateral rotation and abduction of the hip, flexion at the knee and eversion and flexion at the ankle and foot complex. Can be severe and result in contractures, common aggravating factors include bladder infections and pressure sores. Most frequently seen in patients with spinal cord injury, cerebral lesions and multiple sclerosis. Primarily seen in the lower limb but can be exhibited in the upper limb/s. A transient spasm usually occurs in response to noxious stimuli.

Flexor withdrawal: is a response that occurs in the person with an intact nervous system e.g. withdrawing your foot away from a pin on the floor. In a person with a neurological impairment, this response becomes more stereotyped and consistent and can occur with minimal stimulus.

Spastic Dystonia: sustained abnormal posture caused by abnormal muscle contraction that can continue in the absence of movement. It is though to be caused by the sustained efferent muscular hyperactivity, dependent upon continuous supraspinal drive to alpha motor neurones (Burke, 1988, Sheean, 1998). It presents in the upper limb with flexion, adducted and internally rotation at the shoulder, flexion at the elbow with forearm pronation and wrist and fingers flexion. The lower limb is extended, internally rotated and adducted, plantarflexed and inverted at the ankle with toe flexion.

The term “spastic dystonia” has also been used to describe an abnormality of posture, which develops during an attempted movement of the limb. The movement presents as a disordered expression of postural synergy which normally positions and stabilises the limb to carry out a localised movement or task (Sheean, 1998).

Associated reaction: involuntary activation of muscles remote from those normally engaged in a task, e.g. flexion of the upper limb during sit to stand.

Flexor withdrawal reflexes: normally a protective reflex that can be initiated by a painful stimulus such as a hot object touching the hand. Can be seen in the leg following brain injury following an ordinarily non-noxious stimulation to the sole of the foot, which produces flexion of the hip, knee and ankle.

Positive support reaction (PSR): a static response of the lower limb evoked by stretch and pressure on the sole of the foot e.g. during sit to stand or when attempting to step. It produces a rigidly extended limb (Edwards, 2002). There are two possible stimuli that may provoke a PSR:

- a proprioceptive stimulus from a stretch applied to the musculature of the lower limb, especially the foot

- an exteroceptive stimulus triggered by contact with the supporting surface (Magnus, 1926).

Extensor thrust: usually seen in patients following severe head injury and in some patients with multiple sclerosis. Initiated by contact of the back of the head on a supporting surface and causes extension of all four limbs and in severe cases extension of the neck and back.

Negative features:

Described as impairments of normal behaviour, resulting from insufficient descending inputs converging on the motorneurone population to shape complex movements by graded activation of co-ordinating muscles or to bring motor neurones to the high frequency discharges necessary for contraction strength.

Weakness: inability to generate and sustain the necessary force for effective motor behaviour and resulting in impaired timing of force generation relative to the task. It occurs due to the loss of motor unit activation, changes in recruitment ordering and firing rates (Carr & Shepherd, 2003).

Fatiguability: due to transformation of motor units into a unique class of motor units, which are slow contracting and fatiguable and not found in normal muscle. This helps to explain the clinical observation of poor endurance and reduced cardiovascular fitness. However, the changes to muscle and motor unit may occur as a result of disuse as well as diminished neural activation and therefore could be viewed as an adaptive feature of UMN syndrome (see below).

Loss of dexterity: difficulty in making independent movements e.g. tasks requiring fine manipulation, due slow movements and an inability to grade force production resulting in difficulty in building up tension at the initiation of a task and changing the degrees of contraction in prime movers and synergists during the task.

Loss of cutaneous reflexes: these are elicited by gentle cutaneous stimulation e.g. stroking the skin on the lateral abdomen above, below or to the side of the umbilicus which produces a reflex contraction of the abdominal muscles causing the umbilicus to move towards the stimulated side. These are absent following corticospinal tract lesions.

Adaptive features:

Hypertonus: resistance to passive movement. As stated above hypertonia may have neural (active muscle contraction, including spasticity) and non-neural biomechanical elements (reduced soft tissue compliance affecting muscle, tendons, ligaments and joints). Biomechanical hypertonia is not velocity dependent unlike spasticity. Changes in muscle fibre properties and remodelling of the viscoelastic properties of soft tissue increase tone but will allow full passive range of movement albeit with an increased resistance to movement (Carr & Shepherd, 2003, Sheean, 1998).

Contracture: muscle contracture represents the extreme form of biomechanical changes in that there is fixed shortening of the muscle and reduced range of movement. Contractures result from prolonged maintenance of a muscle in a shortened position and could be equally due to poor positioning of a weakened muscle or sustained postures from spastic dystonia.

Parkinson’s disease

Positive features: release of brain mechanisms normally modulated by the basal ganglia.

Rigidity: abnormal muscle tone characterised by resistance to passive movement, generally unaffected by movement velocity, does not involve an exaggerated tendon jerk and is distributed equally in agonist and antagonist (lead pipe rigidity). Rigidity is associated with lesions of the basal ganglia especially in Parkinson’s Disease.

Cogwheel rigidity: when the limb is moved there is resistance that is released in an intermittent way giving the feeling of a cog (hence the name).

Tremor: rhythmical mechanical oscillation of a body part, tremor at rest is a cardinal sign of Parkinson’s disease.

Negative Features: attributed to the loss of function of specific neurones.

Akinesia: a lack of movement, which affects the performance of all motor actions and their associated postural adjustments, e.g. reaching, and manipulation, articulation and phonation.

Bradykinesia: poverty of voluntary movement, slowness in initiating and carrying out motor acts e.g. difficulty reaching a target with a single continuous movement, rapid fatigue accompanied by a reduction in speed and amplitude with repetitive actions.

Adaptive features: slowness of movement and rigidity of posture may reflect an adaptation to pathological postural responses rather than primary deficits in themselves however further work is required to clarify this. Postural instability, characterised by stooped posture is dominated by flexor tone.

Cerebellar Disease

Ataxia: lack of co-ordination of muscle co-contractions causing difficulty timing, sequencing and grading force generation. Movements are clumsy and gait is unsteady and exhibits a wide base of support. Ataxia is commonly associated with cerebellar lesions, multiple sclerosis, Friedrich’s ataxia and head injury.

Symptoms associated with cerebellar ataxia:

Dysmetria: an excessive extent of movement or overshooting (hypermetria) or a deficient extent of movement or undershooting (hypometria). Seen as an inaccurate amplitude of movement and misplaced force, reflecting impaired timing of force generation.

Rebound: problem with braking of movement. Demonstrated by asking the individual to flex the elbow isometrically against the examiner’s resistance, when the resistance is suddenly released the person is unable to stop the resultant movement, the limb overshoots and rebounds excessively.

Dysdiadochokinesia: difficulty performing rapidly alternating movements, e.g. pronation and supination, which worsens with repeated attempts.

Tremor: an oscillatory movement about a joint due to alternating contractions of agonists and antagonists. Intention tremor occurs during movement of the limb and not at rest. Typically the tremor gets worse towards the end of a goal directed movement.

Dyssynergia: a lack of co-ordination between agonist and antagonist and other synergists resulting in an absence of the smooth sequential performance of muscle action, e.g. heel to shin test. It is characterised by the incoordination of movement involving multiple joints.

Hypotonia: diminished resistance to passive movement, although the mechanism behind this remains unclear. Patients with cerebellar lesions do not complain of weakness but some tests are suggestive of this e.g. tendency for the limb to drift downwards when the individual attempts to hold the arm up against gravity, but production of maximum force does not appear to be affected. An inability to sustain force may account for the apparent weakness.

Dysarthria: a disorder of speech articulation where the mechanical aspects of speech are impaired. Patients with ataxia have slow, slurred speech with prolonged syllables (scanning speech). Co-ordination of breathing may also be affected resulting in poor breath support for long sentences.

Nystagmus: associated with damage to the flocculonodular lobe of the cerebellum, seen as rhythmical eye movements.

Communication and Swallowing Problems

A speech and language therapist (SALT) is the specialist therapist who should assess and treat these problems. Physiotherapists can help to advise on optimal positioning for swallowing and voice production.

Aphasia: refers to complete loss of all language both receptive and expressive, now often used interchangeably with dysphasia.

Dysphasia: refers to partial loss of communication skills resulting in difficulty using language. It may and usually does affect both comprehension (receptive dysphasia) and expression (expressive dysphasia).

Comprehension: patients cannot understand the spoken word, may also have difficulty reading.

Expression: patients have difficulty expressing themselves, or in milder cases can not find the words that they want, writing will also be affected. They may be able to use gesture or picture charts to help convey their meaning.

Dysarthria: difficulty speaking due to weakness, lack of co-ordination, +/or loss of sensation of the muscles in the face, lips, palate, tongue and larynx. The patient presents with slurred and hyper-nasal speech, a flattened, dull voice pattern.

Dysphagia: is a problem with swallowing. This can be a serious problem causing risk of aspiration of fluids or food, which may result in pneumonia or asphyxiation. If it persists the patient may be unable to meet their nutritional requirements orally and will require to be fed via a gastrostomy tube or naso-gastric tube. Other patients may only require modification of their diet for example thickened fluids and pureed food. Difficulty chewing and infrequent or inefficient swallowing can cause drooling and choking on food or drink.

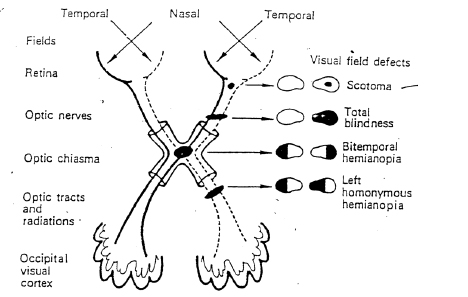

Visual field deficits (refer to diagram)

A lesion in the central part of the optic chiasma, where fibres from the nasal halves of the retina cross each other, results in blindness in the temporal halves of the visual fields; bitemporal hemianopia. A lesion anywhere behind the chiasma will affect the temporal field of one eye, and the nasal field of the other; homonymous hemianopia, always on the side opposite to the lesion. Clinically visual field deficit is seen when the patient fails to scan across a whole page when reading i.e. misses the extreme right or left of the text. However compensation for hemianopia, in the absence of visuospatial neglect, is good.

On the left are listed the anatomical divisions. The black marks show the site of various lesions and the visual field deficits which result are shown on the right.

Cognitive Problems

Associated with damage to the frontal +/or parietal lobes. Cognitive skills involve learning, reasoning, processing and higher level understanding. Cognitive problems may manifest as poor memory, problem solving, reasoning, planning, slow information processing, limited insight and poor judgement, and difficulty learning. The occupational therapist and the clinical psychologist assess and treat these problems. It is important for the rest of the team to understand how these problems affect physical activities to adapt treatment appropriately and to recognise that the behaviour is related to the cognitive deficit and not because the patient is being difficult. This is covered in more detail in HH2125.

Memory:

The ability to take in, store and retrieve information. Attention (memory of a few seconds duration), short-term memory (memory of a few minutes duration) and/or long-term memory may be affected. This will influence the ability to remember things for example, instructions in a therapy session, or what was learnt in the last session, people, places and events or how to find their way back to the ward.

Perceptual Problems

Perception is the ability to interpret sensation. This is needed to give meaning to, and to understand one’s environment. Perceptual problems are associated with lesions of the right parietal lobe. Typically perceptual problems will affect how the patient moves and interprets his surroundings so it is necessary to adapt physiotherapy techniques to account for perceptual problems.

Agnosia: failure to recognise previously familiar objects although sensory (visual, tactile and auditory) systems are unimpaired. Visual agnosia is most obvious, but can also affect smell, sound or touch. It may also include loss of body image when the patient does not recognise part of his body (usually his affected arm or leg).

Dyspraxia: is a cognitive disorder of motor planning disorder and is the inability to carry out a familiar movement in the absence of motor or sensory impairment. This may be because the patient does not have a concept of what is required (ideational apraxia), and/or cannot recall, select or initiate an appropriate movement sequence (ideomotor apraxia). This may lead to errors in the timing, planning, spatial organisation and sequencing of purposeful movement. Often the patient can perform automatic tasks but cannot do the movement to command, in an unfamiliar surroundings or tasks. For example, dressing dyspraxia is where the patient understands the purpose of dressing but is unable to complete the task even though they have normal sensation

Spatial awareness: the ability to know where each body part is in relation to the immediate environment

Visuospatial neglect/inattention: an inability to respond to stimuli presented to the hemiplegic side. This occurs in the absence of any visual field defect. This can be seen clinically in many ways for example washing or dressing only the unaffected side of the body, or eating from only one side of the plate. More common following right parietal lesions. May be called unilateral neglect.

Behavioural Changes

Changes in behaviour become a problem when they are abnormal or inappropriate for the situation e.g. exaggerations of normal behaviour or new abnormal behaviour. It is very context specific and socially and culturally defined. The patient’s pre-morbid behaviour, and the staff’s expectations and pre-conceptions about what is normal and acceptable must be taken into account. Behavioural problems are seen most frequently in people with head injuries.

This may manifest as increased irritability and a decreased threshold to frustration and stress causing outbursts of verbal or physical aggression in response to levels of stress that would normally be considered trivial.

Alternatively some people become very passive and inactive with a decreased motivation and drive.

Disinhibition is not uncommon which may take the form of inappropriate comments, suggestions or behaviour.

Personality changes are also common, the patient’s relatives are often more aware of this than the patient. Most commonly, people become more extrovert, out-going, often more short-tempered and irritable, but sometimes people change to become introverted and quieter. People may be unrealistic about their abilities and lack insight into their situation that can have implications for safety. This subject is covered in more detail in HH2125.

Psychological and Emotional Consequences

For most people a neurological illness or injury is a major life event often with long-term consequences, the emotional impact can be profound and can have a strong effect (either positive or negative) on the effectiveness of rehabilitation. If physical progress is not in line with physical ability then the negative effects of psychological or emotional factors are worth considering.

Depression: this is common and may be due to the pathology or it may be secondary to the consequences of illness/ injury that can cause major life changes. It can occur at any stage although there is a tendency for it to be more common in the first year.

Assessment of mood should be an integral part of the multi-disciplinary team assessment.

It is common for the patient or family to notice emotional changes such as irritability, loss of confidence, loss of interest and pessimistic feelings. These are usually normal reactions to a major life event, but if they become very severe, or prolonged they may be related to an underlying depression. Advice should be sought from a clinical psychologist and the need for short-term antidepressant medication discussed.

Anxiety: is also common and can be an indication of unresolved concerns about illness/injury, and about the future or a manifestation of premorbid anxiety. It is important that health care professionals give appropriate and relevant information, advice and education and this may need to be in conjunction with a clinical psychologist.

Emotional Lability: presents in the form of excessive crying (or rarely laughing) and is often associated with lesions causing dysarthria and dysphasia. This is seen most commonly in people with stroke. It is part of the pathology - not an emotional reaction. It happens because the control of emotions and the threshold for upset is reduced. It does not necessarily mean that the patient is very upset if they suddenly start to cry. It can make social interaction difficult.

Bibliography

Burke, D. (1988) Spasticity as an adaptation to pyramidal tract injury. Advances in Neurology 47: 401-423

Carr, J and Shepherd, R (2003) Stroke Rehabilitation. Guidelines for Exercise and Training to Optimise Motor Skill, Butterworth Heinemann, China.

Edwards, S (2002) Neurological Physiotherapy, A Problem Solving Approach, Churchill Livingstone, London.

Lance,J.W. (1980) Symposium synopsis. In: Feldman R.G., Young,R.R., Koella, W.P. (eds) Spasicity: disordered motor control. Year book, Chicago.

Lindsay, K.W.,& Bone, I. (2004) Neurology and Neurosurgery Illustrated. 4th edition. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.

Magnus, R. (1926) Some results of studies in the physiology of posture. The Lancet, Sept 11: 531-535

Refshauge,K., Ada,L. & Ellis, E. (2005) Science-Based Rehabilitation. Theories into Practice. Elsevier Mosby, Edinburgh.

Sheean, G (1998) Spasticity Rehabilitation, Churchill Communications, London.

Stokes M (2004) Physical Management in Neurological Rehabilitation. 2nd edition. Elsevier Mosby, Edinburgh.